Give for the Gold

Shabani Omari prods open a piece of burning charcoal, sorts through the dirt and lifts a speck of gold the width of two palm lines to reflect the setting sun.

It's a final step in the hours-long process of gold mining. First Omari's workers hack rocks from deep within holes an axe-swing wide. Above, two workers crank bags of the wet, glittery ore to the surface like buckets of well-water. Women, resting from their duties of cooking and cleaning, whack the fist-size rocks against each other to make pebbles, then men dump the pebbles into a roaring, rotating drum big enough to grind an armchair. The din of the drum and its diesel generator overpowers discussion, so Omari's workers labour in deafening silence.

After hours of stone-grinding cacophony, a man and a woman carry the resulting powder in a large bucket to be refined. A teenager pours water onto the powder and sends it over a cloth that retains golden bits while some dirt washes away. Omari himself shakes the wet powder from the cloth onto a pan wider than his waist, hunches his long figure over a pool of mercury-laced water, dunks the pan and patiently swirls the water and dirt together. As mercury latches onto particles of gold and amalgamates, Omari carefully pours worthless sand out of the pan. He places the remaining bead of gold and mercury, half as big as a grain of rice, onto a small cloth, folds it closed and twists as much mercury as he can back into the pool. A helper fetches a warm piece of charcoal and Omari fits the mercury-gold particle into a burning crack to evaporate the mercury, leaving near-pure gold behind.

This grain of gold will fetch about 2,000 Tanzanian shillings — the equivalent of $1.25 Canadian. The 60 or so workers start their shifts every day at 6 a.m. and end at 7 p.m. After selling a week's worth of gold to a trader, Omari will pay the equipment rental fees and the village's levy, and he and his workers will share what's left.

Some days are more golden than others, but miners don't net any long-term savings. As a result, they're mostly transient. This year Omari is the boss of the Bumbiti village mine, last year he was a farmer and 20 years ago he dug at a mine one village away, a half-hour's walk northwest from Bumbiti past short trees, tall grasses, grazing cows and newly-fabricated homes.

That neighbouring mine is now run by the world's biggest gold mining company, Barrick Gold. As the Canadian giant settles into one of Africa's poorest nations, Tanzanians from Omari to the president are asking: what's in it for them?

Barrick says it has the answers.

Opening a country

It's ironic: 35 years ago, Tanzania was the last African country you'd expect to host a multinational. It was the continent's model socialist nation.

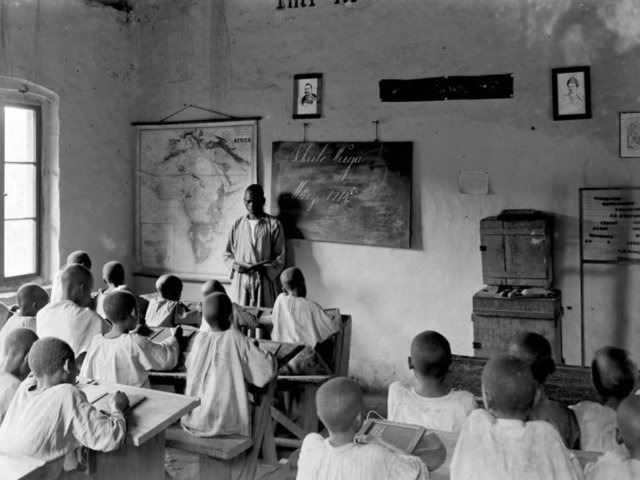

Germany established the protectorate of German East Africa in the late 1800s, including Tanganyika, an area the size of British Columbia on Africa's east coast. Germans created a new government and pioneered a Western education system to train natives to work for it, though they didn't settle in large numbers. After Germany's defeat in World War I, Britain won control of Tanganyika and its 4 million residents. It introduced high schools and education subsidies, and it set up a new police force.

After World War II, Tanganyikans joined the post-war pan-African push for independence from Europe.

The father of the nation

Tanganyika found its champion in Julius Nyerere, a high-school teacher who earned a Master of Arts degree in economics and history from the University of Edinburgh in 1952. In 1954 he quit teaching in Tanganyika's capital, Dar es Salaam, to chair a nationalist political party. Tanganyika won its independence in 1961, and Nyerere became prime minister with Britain's blessing. In 1964 Tanganyika united with the nearby Zanzibar islands to form Tanzania, and Julius Mwalimu (“the Teacher”) Nyerere, the sole candidate, was elected president.

Nyerere was idealistic, anti-capitalist and anti-colonial from the beginning. He broke diplomatic ties with Britain for its refusal to oust Ian Smith's white-majority regime in Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe. He refused West Germany's demand that he deport East German representatives from Zanzibar and he supported a violent Congolese rebellion led by Cuban revolutionary Che Guevara against Joseph Mobutu, the United States-implanted dictator who emerged victorious and transformed Congo into today's “bleeding heart of Africa” (as TIME coined it in 1999). These three western superpowers happened to be Tanzania's major donors, and they responded to his slights by holding back aid. Nyerere told his people the foreign aid dollars were keeping Tanzania from its full potential anyway.

Within Tanzania's borders, Nyerere became worried when he saw an upper class emerging. “Many leaders of the independence struggle ... were not against capitalism,” he wrote in one of his many essays about the challenges facing his country. “They simply wanted its fruits, and saw independence as the means to that end.” Nyerere set his own salary at an exemplary 4,000 pounds per year, lower than that of some cabinet ministers. Tanzanians lauded him, and TIME magazine wrote in a 1964 cover story that he was “considered Africa's most sensible and sensitive statesman.”

Nyerere believed African culture was socialist and that development should start in villages, not the city, so he invented a system called Ujamaa (“family-hood”), nationalizing banks, insurance companies, food processors, trading companies, apartments and even houses, and moving Tanzanians into new, collectivist villages.

Few Tanzanians relocated voluntarily. Police, army and militia coerced them in 1974, burning homes to force people to move. The new land wasn't ready to be farmed and the new inhabitants, accustomed to farming alone, were inefficient in collectives. Food production dropped and Tanzania ran out of money. Nyerere was forced to rely on donors for food aid and payments for imports, which the United States, Nordic countries and China provided — a cross-section of Cold War superpowers.

It got worse: Ugandan dictator Idi Amin invaded Tanzania in 1978, complaining that the country sheltered Ugandan rebels. The Tanzanian army and Ugandan rebels swiftly invaded Uganda and overthrew Amin in 1979. The victory depleted what remained of Tanzania's coffers. By 1982, far from being a nation of self-sufficient villages, Tanzania was accepting $600 million in foreign aid per year, more per capita than any other African country.

Nevertheless, Nyerere was and still is widely admired. Ask most of Tanzania's 44 million citizens about him today and Nyerere will be described as on par with Nelson Mandela or Mohandas Gandhi. He directed unconventional progress that set Tanzania apart from its neighbours. “The Teacher” boosted primary school enrolment from 25 per cent to 95 per cent and he promoted harmony among Tanzania's more than 130 tribes by encouraging government employees and students to work and learn in regions far from their tribal homes. When he realized Ujamaa was doomed, he retired voluntarily on the eve of the 1985 election, saying in his farewell speech after 23 years as president: “I failed.”

Structural adjustment

With Nyerere's tacit okay, incoming president Ali Hassan Mwinyi asked for money and the West brought it — realizing the former president's worst fears. The Washington-based World Bank and International Monetary Fund offered new country-saving loans with their trademark 1980s quid pro quo. To receive the loans, Tanzania's government had to conform to western economists' “structural adjustment” reforms. The government introduced school fees, and primary enrolment plunged from 95 per cent to 67 per cent in 1999. It floated the exchange rate, and prices rose an average of 30 per cent per year between 1986 and 1992. It privatized everything from electricity management to water to farms. Private utility companies raised prices and lowered service, so the government eventually reclaimed them. Private rice farms fared better, quadrupling production since the state sold them, but those surplus grains fed exports, not the 58 per cent of Tanzanians living on less than a dollar a day (according to a government 2001 survey). The World Food Project reported in 2010 that over one-third of children in rural mainland Tanzania are stunted.

To turn it around, Tanzania is looking to its exports.

Tanzania has exported coffee, cashews and cotton since colonial times. Nyerere's vision was a farming nation, and today farming accounts for 80 per cent of Tanzania's jobs and 85 per cent of its exports.

That's changing. Western influence opened the country to foreign investment, and international companies see more in Tanzania than farmland. They see oil, uranium, copper, diamonds, gemstones and gold.

The seeds of mining

At first, foreign companies didn't build mines. Rural miners would dig for gems and gold and sell them to Tanzanian merchants in Dar es Salaam, the country's financial capital, in the 1980s. The merchants would then export them with a government license. The central bank began offering to buy the gold directly in 1990, a boon for local miners.

In the later 1990s, foreign investors moved in. One early gold mining company was Vancouver-based Sutton Resources. Through a local company, Sutton Resources acquired several mining licenses, including one to build a gold mine, Bulyanhulu, in Western Tanzania.

Bigger deals were yet to come, and capitalist reforms paved the way. During a five-year World Bank “sectoral reform project,” parliament passed a new Mining Act in 1998 to replace Nyerere's law of 1979. The Act gave foreign-owned companies the right to hold mining licenses in Tanzania, took away ministers' right to deny licenses, required the government to collect and freely distribute geological data to mining companies, guaranteed the government wouldn't impose new taxes and prevented the state from nationalizing mines without consent. These changes catered to foreign investors, who see Africa as a continent of risk. The changes were supported by the International Monetary Fund, whose directors discussed Tanzania's mining reforms and other pro-capitalism policy changes before granting it $3 billion in debt relief in 2001.

In 1999, one year into the new Mining Act, Toronto-based Barrick Gold bought Sutton Resources and the unfinished Bulyanhulu underground mine on its path to becoming the world's biggest gold mining company.

Barrick Gold

Barrick Gold is the creation of Peter Munk, an engineer from a well-off Hungarian family that fled to Canada during World War II. Munk founded Barrick and took it public in 1983 on the Toronto Stock Exchange. The company acquired a mine a year in its first four years, then it expanded into South America in 1994 by purchasing Canadian company Lac Minerals, gaining ownership of mines in Canada, the United States and Chile. Barrick acquired a gold deposit in Peru in 1996.

Barrick bought Sutton Resources in 1999 to obtain its first African gold mine. Barrick purchased Toronto-based Pangea Goldfields in 2000 to acquire two more Tanzanian gold mining licenses. It opened Sutton's Bulyanhulu in 2001, making Tanzania the third-largest gold producer on the continent after South Africa and Ghana. (Mali edged it out since then, and today Tanzania is the fourth-largest.) Barrick took over Vancouver-based Placer Dome in 2006 for an interest in 16 gold-mining operations in seven countries, including one in Tanzania, making Barrick the world's largest gold mining company.

Barrick Gold Corporation spun off its Tanzanian projects into a new London-based company, African Barrick Gold, in March 2010. Barrick Gold Corporation retained 74 per cent ownership of the London company and sold the rest for £581 million in an initial public offering on the London Stock Exchange.

Barrick Gold Corporation now holds shares of 25 mines on four continents. In Tanzania African Barrick Gold operates four mines, which produced 701,000 ounces of gold in 2010. Canada's Barrick Gold Corporation counts 564,000 of those Tanzanian ounces as its own, roughly 7 per cent of the 7.8 million ounces it produced worldwide that year.

It's the right time to be mining. The price of gold climbed to $1,430 in March 2011 from $270 (USD) in 2000. Investors turned to gold when a financial collapse and recession swept across much of the world, and there's no sign the boom is temporary. Gold deposits which would have cost too much to extract ten years ago — like some in Tanzania — are now worth the expense.

Barrick Tanzania

To Barrick, Tanzania offers a balance between risk and reward not found in other African countries.

There's plenty of gold and not much competition. Aside from Barrick, the major players are Resolute Mining Limited, an Australian company which opened the Golden Pride mine in 1999, and AngloGold Ashanti, a South African giant that opened the Geita mine in 2000. African Barrick Gold produced about twice as much gold as AngloGold Ashanti and four and a half times as much as Resolute in 2010.

Not only is competition scarce in Tanzania, but its business world is more predictable than in neighbouring countries. Mines in Democratic Republic of Congo could be seized by corrupt officials or even attacked by rebel groups. Mines in Uganda are at the mercy of a president many see as autocratic and mines in Kenya could witness a repeat of the tribalism-tinged 2007 election violence that killed hundreds and halted business for weeks.

Tanzania, on the other hand, hasn't seen major tribal violence since independence. Virtually all its citizens speak Swahili, the language Nyerere promoted.

But for Barrick there's one downside to national unity. Most Tanzanians speak neither English nor profit, Barrick's two native languages. At the end of 2010 the company was paying four thousand employees and thousands more contractors, mostly Tanzanian — but most Tanzanians, in Nyerere-inspired unison, see Barrick as a suspicious foreigner.

Bulyanhulu

The first situation at a Barrick mine happened in the remote villages surrounding Bulyanhulu, before Barrick even arrived in Tanzania. Local miners stayed even after their host villages sold their mining rights to Sutton Resources. In 1996 Tanzanian police shooed away miners and their families who were now illegally digging Sutton Resources' gold and living on Sutton Resources' land. According to legend, dozens of miners returned and descended into their holes in protest, where a company bulldozer buried them alive.

That's the claim Barrick inherited it when it bought Sutton Resources. Barrick sued the Observer in England for printing it. Amnesty International reported killings in 1997 but backed off later, admitting in 2001 it was “unable to substantiate the allegations of deaths.” Canada's National Post reported a 4,255-word story on the controversy in 2001 and detected no malpractice, and a 2002 World Bank investigation also found no evidence of wrongdoing.

The allegations and legal battles persist. Noir Canada, a book published in Quebec in 2008, repeated the story. Barrick is suing the book's non-profit publisher, Éditions Écosociété, in a $6-million defamation case. The trial is scheduled to begin in September 2011.

But in Tanzania, neither Sutton nor Barrick sued the media for publishing and broadcasting the story locally. Instead, Barrick deflated negative attention with philanthropy. When villagers vandalized a Barrick-built water pipeline to access the water within, Barrick decided the most productive solution was to build free taps along it. To stave off accusations that big mines boost prostitution and thus spread HIV, Barrick built an HIV awareness clinic that supplies free condoms to everybody. Barrick brought electricity, a school and a road to thousands of villagers near its mine.

Barrick's image

Today, production at Bulyanhulu is rarely interrupted. Many Tanzanians still believe Barrick is responsible for deaths in 1996, though.

“It always comes up,” complains Teweli Teweli, Barrick's spokesperson in Tanzania, who denies Barrick or Sutton is responsible for any extrajudicial killings. “This is an issue we've been addressing and we keep on addressing, but I think the evidence on the table is overwhelming.”

Teweli is the bridge from Tanzanian journalists to Barrick. He calms fires in the Tanzanian media in English and Swahili. He's a gold-mining spokesperson without a gold watch, a former tobacco spokesperson who didn't smoke. In English, his accent is unplaceable: he doesn't draw out Es and Is like a typical East African, nor does he hide his Rs as his teachers did in the United Kingdom, where he was schooled. His voice is enunciated but neutral, and he'll speak calmly and precisely even when journalists level criminal allegations against his employer. He's equally clear in Swahili, the language he uses most often with the media.

Tanzanian journalists harass him endlessly for print, radio, television and online reports. Lately the focus has been the North Mara mine, which opened in 2002 and which Barrick inherited in 2006 when it acquired Placer Dome. Guards and police at the site shot and killed several trespassers over the years. In 2008 police shot one person dead when hundreds of villagers broke in and destroyed about $7 million worth of equipment, according to Barrick and local media. In May 2009, acidic water seeped from a Barrick facility at the mine into the nearby river, an “isolated incident” according to Barrick, “exacerbated by the theft of some of the impermeable material used to line waste water ponds.” For each event, Teweli appears as the voice of Barrick in news reports.

Last year journalists ambushed Teweli in a television interview, presenting two villagers who showed their discoloured skin and blamed it on the North Mara leak. The next week Teweli returned to the show with a doctor's analysis of pictures of their skin. The doctor suggested the villagers had had skin problems for years and that their disease couldn't have been caused by toxic water, but the villagers didn't appear on television to face Teweli's rebuttal.

To improve Barrick's image, Teweli started hosting free media tours for Tanzanian journalists in 2008, flying dozens to all four mines to dispel myths and show them the positive aspects of Barrick's activities.

Teweli watches the news and offers the tour to reporters he notices are particularly biased. “I would say maybe five out of 10 of those (journalists) either end up not writing a story at all because they're surprised with what they've run into, or they do write a story but it's not as strong as some of the other stuff we find on the Internet that they've already written,” he says, donning a hard hat and leading four print and radio journalists to a processing plant tour.

Showing off

But Teweli can't win over journalists with the chemical smells of a processing plant grinding gold-speckled rocks for export to Asia. And he can't do it with numbers alone. The Tanzanian government hopes mines will account for 10 per cent of its GDP by 2025, but it's hard to trust figures in Tanzania. This February, for instance, the government collaborated with mining companies to finally disclose receipts. Companies reported paying $84.4 million to the government in the 2008-09 budget year and the government reported receiving $48.3 million.

Rather than numbers, Barrick needs concrete and current offerings to prove it can provide long-term benefit to the country.

So Teweli shows off Barrick's non-financial impact: water taps, electricity lines, houses, schools and jobs. Barrick started some projects, such as 10 primary and two secondary schools, as newsworthy offerings to villages surrounding all its mines. Others, such as dozens of taps pouring clean water for hundreds of families near Bulyanhulu mine, are pragmatic solutions to security problems. No matter what the incentives, the projects all fit Barrick's “Corporate Social Responsibility” charter.

Corporate Social Responsibility

Corporate social responsibility has different meanings in different contexts. Industry Canada defines CSR as “the private sector’s way of integrating the economic, social, and environmental imperatives of their activities.” Those three PowerPoint-ready pillars, “people, planet and profit,” are nothing new. Milton Friedman, the famed American free-market professor whom the Economist names as possibly the most influential economist of the 20th century, described CSR in 1970 as “pure and unadulterated socialism” and a “fundamentally subversive doctrine” since it can hinder businesses from acting in the interests of their shareholders.

Recently, after Canadian activists raised allegations of human rights abuses from Canada-run mines around the world, including Bulyanhulu, Canada's mining sector has placed greater emphasis on CSR in public. In 2007 Canadian mining companies and non-governmental organizations began meeting periodically in a forum called the Devonshire Initiative that gives the companies advice on responsible mining. In October 2010 the federal government appointed Marketa Evans as Canada's first “CSR Counsellor” for the extractive sector, tasked with helping Canadian companies manage projects overseas.

Two notions pervade today's definitions of CSR. The first is that corporations should provide benefits to more than just their shareholders. The second is that CSR is optional.

Barrick chooses to embrace CSR. Its global “CSR Charter” quotes a World Bank definition: “working with employees, their families, the local community and society at large to improve the quality of life, in ways that are both good for business and good for development.” Barrick's charter has four components: Ethics, Employees, Community, and Environment.

Ideas from the Barrick's charter reach Tanzania. As Teweli says while showing journalists his company's projects, “there's never been a mine without a community.”

The communities Barrick creates through CSR aren't what Nyerere wanted, since they focus primarily on the interests of the corporation. Moreover, they aren't what Canadians or Tanzanians expect. Behind the company's quest for making good local, national and international impressions, blind spots affect both Barrick and its critics.

The big fence

As one example, CSR suggests buying goods and services locally and Barrick Tanzania has taken that advice. That's why Kashindye Hassan, of Chapulwa village, took a job with Barrick's locally-procured militia at the Buzwagi mine.

Buzwagi, Tanzania's largest open-pit mine, started producing gold in May 2009. Construction started in 2007 and it was Barrick's first opportunity to build a community from scratch in Tanzania. Barrick inherited its other Tanzanian mines from previous owners.

This mine is different. Barrick's others are remote, but as luck would have it, the gold-rich ground of Buzwagi is a ten-minute minibus ride from Kahama, a town five kilometres to the west of the mine site. At night, lights from the mine brighten the main road, which stretches from Rwanda, the neighbour 250 kilometres northwest, to Dar es Salaam, the seaport 1,000 kilometres to the east. More than merely visible, Buzwagi is a beaming display of wealth beside a poor town.

Kahama

The town of Kahama, population 46,000, situated in the district of Kahama, is the last major Tanzanian stop for Rwanda-bound truckers. Its dirt roads grow undulations daily from the bicycles, “piki-piki” motorcycles and 18-wheelers weaving around each other. The streets are lined with hotels named after inaccessible lands of imagined prosperity: California Garden Bar and Guest House, Manyara Lodge, Miami Beach Hotel. Stacked Coca-Cola crates stand guard outside the restaurants and shops, serviced by trucks that supply fresh soda and collect empty bottles. West of town, a cluster of barn-sized buildings hides roaring rice-husking machines, preparing the grains for transport. Nearby, government offices serve the needs of the 800,000 people in the district.

Outside the town's bustle, villagers live off the savanna. Dusty paths meander among the homes and cattle graze on the grassy distances between houses. Families are somewhat nomadic. Every few years a man might move his herd to some unclaimed land to build a new mud hut, and if his cows seem happy he'll bring his wives and children after a year or two. Only 30 per cent of homes have access to clean and safe water, and the most recent budget survey in the district, conducted in 2000-2001, found per-capita income was 350,000 shillings per year — that's about $234 US at today's exchange rate, or a sixth of an ounce of gold.

Crunch those numbers and you'll find the district of Kahama's 800,000 residents earn a total of $16 million in an average month. In contrast, Buzwagi shipped an average of $22 million worth of gold per month in 2009.

Protection

With so many poor people watching so much money truck its way out of the country, it's predictable that one of Barrick's biggest problems is theft. Barrick uncovered a fuel theft syndicate within its staff and contractors in the third quarter of 2010, and yearly production dropped by about 14 per cent because Barrick suspended and fired some workers as a result. Outside the 25 square kilometres of Buzwagi land, more threats await.

The only hurdle between thieves and prosperity is a fence: a three-metre high barrier of chain links stretching both ways to the horizon, topped with barbed wire. Along the road Barrick has installed two layers of fence and wound barbed-wire as insulation between them. Floodlights and guard towers dot the enormous perimeter.

Barrick hires its own security guards and it contracts guards from private companies as well. Despite the fences and guards, though, groups of thieves stole computers and televisions from the mine on seven occasions between 2007 and 2009.

Police do little more than gather bribes along the road. So in November 2009, Barrick brought in leaders from the three villages next to Buzwagi and struck a deal. This is corporate social responsibility at the village level — not the kind Barrick advertises in Canada.

Protection, with Corporate Social Responsibility

Kashindye Hassan, of Chapulwa village, has a salary. He's clad in grey with a fluorescent-yellow vest, walking his bicycle along a dirt path to meet his neighbours on the patchy lawn outside the village's administration buildings.He and hundreds of his neighbours form Barrick's outer militia: the sungusungu.

On a twelve-hour night shift standing outside the fence, Hassan says he might spot 35 potential intruders. “When they see me, they leave,” he says. Five or six usually try their luck more than once. “If they come back, I call Barrick. Barrick comes and takes them.”

Hassan reports to the sungusungu offices like all his fellow youths of the Sukuma tribe. Barrick pays the village a fee for Hassan's services and Hassan earns the equivalent of $2.25 a day. He uses it to buy things around the house.

“Yeah, 'things around the house!'” his off-duty friend laughs and nudges, staggering in Barrick-supplied boots under the weight of his $0.75 bottle of Kilimanjaro beer.

For Barrick, the sungusungu are perfect: they're cheap, they deter crime, and as a side benefit village leaders are paid so they're happier to have Barrick around. Barrick pays the villages $107 per guard per month and stipulates they need uniforms, food and a recommended $67 monthly salary. Village leadership can skim profit by supplying contracted benefits at under $40 and by taxing the $67 salary. Chapulwa village pays Hassan the entire $67, but neighbouring Mwendakulima village takes a 10 per cent cut from its guards.

Barrick doesn't just win security by hiring sungusungu: it earns a place in the villages. Locals appreciate Barrick's respect of their customs, and Tanzanian reporters from around the country nod in knowing approval when Teweli mentions the deal. Barrick's payments boost the local economy and create — or at least, legitimize — jobs.

Hassan and his fellow sungusungu proudly say they were crime-fighting for free before Barrick came along. That's not exactly true. There's something about the sungusungu that neither Hassan nor Barrick like to mention.

Another kind of risk

Most sungusungu — all sungusungu, except Barrick's — are grass-roots Sukuma crime fighters. Armed, jobless males turned to banditry in the early 1980s after Tanzania repelled Uganda's invasion. Villagers formed “sungusungu” (“biting ants”) militias to protect themselves and their property, armed only with traditional weapons such as bows and arrows. They rid their villages of cattle-rustlers, thieves and adulterers. Today, most youths in the villages surrounding Buzwagi are sungusungu.

Tanzanian law recognizes the sungusungu, but the relationship between police and the vigilantes has always been strained.

“They are uneducated, many of them. They don't know the laws of this country,” says Hussein Salum, the younger of Kahama's two magistrates. “They don't know how to investigate cases. They just use those traditional ways. They just use force.”

In court, Salum sits behind his large desk, pen scribbling notes on paper, Laws of Tanzania always within reach of his left hand. He'll listen to witnesses and weigh their evidence in his office, which is furnished with extra chairs and a bench under the back window so it doubles as a courtroom.

Salum estimates Barrick security and police bring about 30 cases of theft and criminal trespass per month at Buzwagi. He says sungusungu are so untrustworthy nobody even presents them in court as eyewitnesses.

Salum has seen it all: sungusungu regularly accuse suspects without evidence, plant evidence on them to make their cases, or even torture them to extract a confession. Sungusungu tie up suspects and imprison them without food or water, as well as the obvious, “just beating them.”

Salum says he's dismissed cases because suspects complained in court that the sungusungu around Buzwagi beat confessions out of them. The details of these cases are lost in bookcases of write-and-forget court records.

When Manyanda Makomba, a sungusungu assistant commander, is asked about torture, he grins with a “we get that all the time” chuckle and explains in drawled Swahili that the forces he supplies to Barrick don't use violence. His other subordinates, though, behave differently.

“Even the police use violence. So sungusungu work like the police,” says the Barrick-sponsored authority in Mwendakulima village. “It's possible when you're captured you resist. (Sungusungu) tell you to do something and you refuse, therefore they have to 'balance' you so you can sort yourself out.”

“So it's normal for our forces,” he says. “They don't just beat you when you're not guilty.”

Salum says the sungusungu usually avoid courts, for two reasons. First, they become impatient when the law dismisses their planted evidence as inadmissible. Second, “those traditional ways” are profitable.

After assigning guilt, through violence when necessary, Makomba says the sungusungu extract a fine — that's illegal, according to Tanzania's laws, courts, politicians and constitution. The money makes its way to Makomba's office, and the militiamen who brought it earn a cut. With that business out of the way, suspects are run out of town.

“There's no need to send them to the police station,” Makomba says.

Barrick says it's aware of the reputation of sungusungu, but it says the sungusungu who were reassigned to Barrick by commanders like Makomba behave differently. It says sungusungu militiamen bring suspects to Barrick's security guards, who bring them to the police, who bring them to court. Barrick has told each village that any incidents of violence will end that village's entire contract, and it said in February 2010 that no such incidents have occurred.

Where the problem waits

That means the 75 of Mwendakulima's sungusungu who work for Barrick aren't allowed to frisk suspects for cash, while the non-Barrick sungusungu, numbering more than 325, are encouraged to do so. All 400 avoid police, most are uneducated, many use violence routinely and neither the individual guards, the sungusungu chiefs nor Barrick want to hear whispers of illegal violence the entire nation associates with the name “sungusungu.”

Teweli himself admits there are dangers to employing sungusungu. “Normally violence is the automatic response, that's what the community is expected to do,” he says. “Somebody climbs over the fence, you put a mshale through him, an arrow.”

Generally, victims have no recourse because they don't trust or understand Tanzania's legal system. Teweli says it's different with Barrick. If someone was beaten by Barrick's sungusungu, Teweli says, the victim can walk into Barrick's offices and lodge a complaint.

“I'm dead serious, it's working quite well,” he says, speaking of North Mara mine. “We've been getting intruders coming to file grievances because they felt they were abused the previous evening while they were intruding.”

Teweli has seen the process himself at North Mara. “In comes a guy and he says 'I have a grievance to file,'” he says. “When they start filing the case I soon realize that this guy is reporting a security guard who chased him off the previous evening.”

“That's a very, very, very effective way of finding out what's going on,” he says.

Whether it is or not, Barrick says nobody has walked into its Buzwagi offices to complain about being beaten by sungusungu. Only Salum has heard accusations from suspects against sungusungu in court, albeit without evidence.

It's tempting to believe Barrick's case that paying and training the sungusungu may change their tendencies. Unfortunately, there's no impartial observer to confirm that.

Winning hearts, not minds

On a sunny afternoon, dozens of bicycles crowd together on their kickstands under an enormous mango tree. Some are clean and others are caked with the dust that invades every machine in western Tanzania. A few metres across the dirt courtyard, two flagpoles recognize the school's builders: one holds a frazzled Tanzanian flag and the other is unadorned. The Barrick Gold flag was torn down again some nights ago by vandals. Nobody has replaced it this time. Nobody has replaced the soccer goals or basketball nets, either. School administrators say thieves stole them to sell the iron.

The buildings are clean and new. Hammers resound from the far end of campus as workers build new science laboratories and houses for teachers. The mound of dug dirt at Buzwagi mine punctures the flat horizon.

Barrick is paying for the construction of Mwendakulima Secondary School a five-minute walk from the Buzwagi fence. The school bolsters Barrick's reputation abroad, but it ignores the reality on the ground: Tanzania's education system.

Temporary teachers

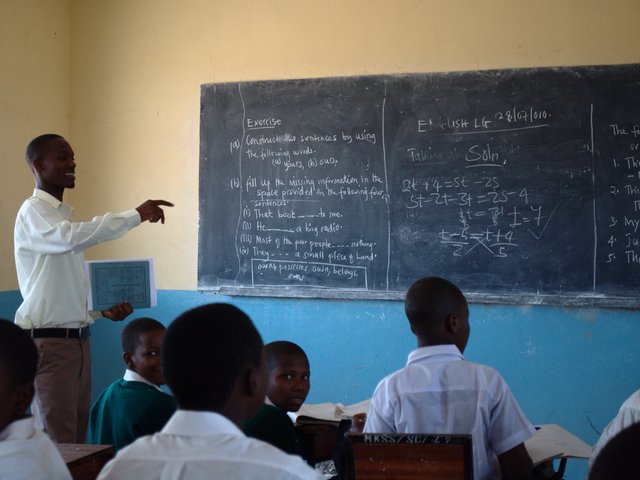

Mgema Nyangisa abandons the courtyard and steps into the shade of a first-year chemistry class. He patrols the front row, asking his pupils if they've done their homework. Under his coaxing smile, the co-ed class of about 35 gradually eases its chattering. Students sit two to a desk, sometimes two to a chair. They open their exercise books and follow along.

There's an exchange of knowledge here, to be sure. But Nyangisa isn't officially a teacher.

Nyangisa, 22, passed his Form 4 standardized tests with Bs in chemistry and biology. He finished his last year of secondary school, called Form 6, near Mount Kilimanjaro 500 kilometres away. He wrote the standardized tests and received Ds in chemistry and biology. Now he's in career limbo.

“The government does not provide employment for Form 6 leavers,” he explains.

Universities don't answer applications quickly. After leaving school, Nyangisa has to wait 8 months to find out whether any of the universities he's applied to will accept him into their medicine programs.

In the meantime, Nyangisa followed the same path as most of his classmates. He moved back to his hometown and applied to teach in nearby secondary schools. Mwendakulima, the third school he applied to, hired him in June as a “temporary teacher.”

Temporary teachers are, as the name implies, temporary. Moreover, they're untrained. Schools in Tanzania and surrounding countries hire them because governments can't afford qualified teachers. On paper the government should provide 16 trained teachers for Mwendakulima's 377 non-absent students. In reality, the school employed eight teachers in 2010. Instead of having only one teacher per 47 students, the school collects fees and uses its funds to hire five temporary teachers like Nyangisa. That gives the more comfortable ratio of one teacher for every 29 students, even though there's no guarantee the temporary teachers have passed high school.

The pay is humble. “The amount is not enough. To say something is enough is to say it satisfies our needs,” says Nyangisa, who lives in town with a temporary teacher from a neighbouring high school and a worker at Buzwagi. “According to our level (of education) it is enough, but according to life it is not enough.”

“Not enough” could be the school's motto, the way teachers and administrators see it. There's no electricity yet. There aren't enough teachers, which is just as well because there aren't enough houses for the teachers who aren't there. There aren't any qualified math or science teachers, and when temporary teachers like Nyangisa leave there won't be any unqualified ones either. There aren't enough desks. There aren't enough chairs. There isn't enough laboratory equipment. There aren't enough books. There's no fence.

Nobody even knows the boundaries of the school's property. Villagers bring their cows to graze outside the classrooms.

As one teacher voices these complaints, a Barrick employee interrupts him.

“There's nowhere where we stated that Barrick was supposed to supply electricity or water, or guarding the area or putting a fence,” says Emil Karuranga, Barrick's community relations manager at Buzwagi. “It's all part of the agreement. The security of the area, because of the handing-over, is property of the school administration of the district. Also, the supply of water and electricity, through our (memorandum of understanding), is the responsibility of the District Council, not Barrick.”

In other words, according to the agreement Barrick made when it offered the district a school, Barrick only handles construction. The rest is up to the Tanzanian government. If Tanzania had a decent education system, this would be an efficient division of labour.

Tanzania's learning disability

But Tanzania's education system is far from decent. It's never been decent. From Germany to Britain to “The Teacher” Nyerere, the main goal has always been to put more students in school. Today, development agencies say that's not as important as actually educating them.

This concern arose when Buzwagi was but a glint in a Canadian's eye. The loudest cry came from HakiElimu (“Right to Education”), a prominent advocacy group created by Tanzanians and funded by development agencies from Sweden, Ireland and the Netherlands. In 2005 HakiElimu parsed government documents and interviewed teachers' union officials and civil society groups and released a report. The report followed Tanzanian culture and began by respectfully lauding the number of new schools in the country. Then it bluntly stated teachers were underpaid and there weren't nearly enough books, desks or teachers for Tanzania's new primary schools. In 2007, the year Barrick began building Mwendakulima Secondary School, HakiElimu researched and reported the same problem in Tanzania's secondary schools, singling out temporary teachers like Nyangisa as a telling symptom. The government temporarily banned HakiElimu from investigating education around the 2005 election, but that got people talking more. HakiElimu says it inspired 1,000 published news articles in Tanzania between 2005 and 2007 about the state of education. Its plain-language message stretched across television and radio, too: Tanzania needs teachers, not schools.

The Ministry of Education detailed its spending last year through an on-the-ground survey. Its report suggests that while the number of secondary students doubled between 2005 and 2008, the annual allocated budget per student dropped from 199,000 shillings in 2005 (USD $216 at that year's exchange rate) to 115,000 shillings in 2008 (USD $97). According to a ministry status report, “the new school units and student enrolment targets were overshot and have impinged on the ability to deliver other necessary inputs.” Only 55 per cent of students who took their Form 4 tests passed in 2010, down from 73 per cent the year before and 84 per cent the year before that.

A new agency recently published the results of its own survey of 42,000 children. The study by Twaweza (“We can”), which advocates government transparency and shares donors and a founder with HakiElimu, suggests one in five Tanzanian students who complete grade seven can't read at a grade two level. It suggests three in ten primary school graduates can't multiply, one in ten can't add and half can't read English, the only language of Tanzania's secondary schools.

The message is the same: rather than focus on building new schools, Tanzania should make the existing ones provide a decent education.

At Mwendakulima Secondary School, 26 students passed the Form 4 standardized test in 2010. All but one were in the lowest pass bracket, meaning they can't proceed to higher education. Another 11 students were absent and 62 failed.

Barrick effects

The district of Kahama ought to have employed 640 teachers in 2010 but there were only 271, according to Gwasa Joseph, the secondary education officer. Even when he factors in temporary teachers like Nyangisa, the total is 440. The government only recruits another 40 teachers every year.

Sending eight teachers to a newly-built school means other schools in the district don't get the eight teachers they would otherwise have shared. There are more classrooms, more students, and a lower-quality education for everybody.

A teacher's minimum wage is about $76 USD per month — the price of a sungusungu guard — but according to Joseph, Barrick kept them out of the contract. “They can't support everything. They can offer what they can afford financially,” he says.

Barrick says it doesn't hire teachers because it doesn't want to pay recurring costs. Recurring costs would vanish when Barrick closes its mines, leaving a hole in government budgets. Barrick expects to close Buzwagi around 2022 and Bulyanhulu, also in Kahama district, around 2034.

Nobody suggests Barrick is hurting the education system — just that it isn't helping as much as it could. Embroiled in controversy in 2001, Barrick gave $2 million to CARE, an international aid group, to improve Kahama's education sector over six years. Primary enrolment increased by 75 per cent, and 89 per cent of students passed their final exams in 2007, up from 16 per cent in 2001, thanks to teacher training and a long-term plan. CARE moved on to other programs and Barrick hasn't expanded this one.

At Bulyanhulu, Barrick built a secondary school as part of the CARE program. There, too, the school's roster of teachers is half-empty. Instead of salaries, Barrick invested in new science laboratories. Now, in 2010, Teweli shows off the shiny buildings, complete with Bunsen burners, a glass-hatched fume disposal chimney and even an outdoor water fountain — not for dispensing drinking water, but for washing students' eyes in case chemicals reach them. The labs cost $184,000, which is enough to hire seven math and science teachers for 28 years at minimum wage. There's one science teacher at the school today.

Barrick's activities, these schools among them, have garnered international praise. In 2008 Barrick was named to the Dow Jones Sustainability Index, which ranks companies based not only on their stock performance but also on their environmental and philanthropic actions. Barrick's schools also improve its relations locally, as the district, villagers and students are happy for the support.

Meanwhile Nyangisa, who learned from novice instructors, is training Tanzania's next generation of unqualified chemistry teachers.

The elites

Kigoma, a quiet port on quiet Lake Tanganyika, sits ten hours west of Kahama by bumpy bus ride.

A man sits in the passenger seat of his Land Cruiser, lap laden with newspapers. The car window is open.

“Hey, Zitto!” calls a passer-by. He walks up and chatters in Swahili about what he hopes will happen in the region. The man, a politician, nods and says he'll do his best.

This isn't even Zitto Kabwe's constituency, but everybody knows his name. Crowds of volunteers pile into truck beds and ride through the streets, blaring music and chanting campaign slogans through enormous speaker systems. They hand out flyers showing Kabwe's picture, Kabwe's accomplishments and Kabwe's election promises, urging residents to vote for Ally Mleh.

That was the party's 2010 campaign strategy in Kigoma Town: convince people to vote for the candidate Kabwe endorses.

It worked in 10 other constituencies around Tanzania's north and northwest, and it almost worked for Mleh. The Kigoma Town contender had never run before and his party's previous challenger finished a distant second in 2005. Mleh lost his bid by a mere three percentage points by riding in Kabwe's shadow.

Kabwe is a household name across Tanzania since he spoke against the Buzwagi contract and Barrick Gold. Barrick later supplied materials for a school in Kigoma North, the remote area Kabwe describes as his “mine-less constituency.”

From suspension to flying

The story began in 2006, before Buzwagi, when president Jakaya Kikwete asked the Minister of Energy and Mineral Resources, Ibrahim Msabaha, to renegotiate all contracts with foreign mining companies. Tanzanians were complaining that mining multinationals, which had yet to recoup their expenses and turn profitable, weren't providing enough tax revenues.

Msabaha began talks with foreign miners and suggested in his 2006-2007 budget that the government would not sign new contracts or renew existing ones until further notice.

During negotiations, Barrick made concessions covering its existing mines. It agreed to advance $7 million a year in taxes even before its mines became profitable. It agreed to pay $200,000 per year to the councils of the districts it operates in and it gave up its tax breaks on equipment and fuel costs.

In February 2007, Barrick had mentioned these concessions but hadn't legally signed on to them. Nazir Karamagi had replaced Msabaha as head of the mining ministry in a cabinet shuffle, and the media were still criticizing mining contracts.

Then came a new one. On Feb. 17, Karamagi signed the brand-new contract that let Barrick develop Buzwagi. His signature seemed poised to propel controversy to new levels, but Karamagi had a plan to defuse the situation.

He didn't tell anybody.

Barrick mentioned the contract in its 2006 annual report, which it released to shareholders and the public on Feb. 22, 2007, but it seems nobody in Tanzania read it. There wasn't any activity on the ground in Kahama to make residents suspicious because Barrick needed to wait for an environmental assessment of its proposed mine site. Karamagi remained mum.

“It was signed secretly. It was signed in London, in a hotel room, at midnight,” says Kabwe, emphasizing each fact with a pause. “No single member of parliament knew about this. The parliamentary committee on mining didn't know about it.”

Kabwe found out about the Buzwagi contract that July, tipped off by a “concerned Tanzanian.”

“I brought up the issue in Parliament. I asked the minister, 'did you sign this contract?' and the minister initially said 'no, I did not.' Later, he said yes. So he flip-flopped.” Kabwe announced that the minister had lied, and he criticized the minister for refusing to let Parliament examine the contract when asked. He moved to censure Karamagi and requested a committee be created to examine the deal.

But that doesn't happen in Tanzania. Kabwe, the country's youngest MP, was an opposition member whereas the ruling party held 206 of the 232 elected seats. Ruling-party politicians ganged up and suspended Kabwe from Parliament within hours for humiliating the mining minister, effective from August 2007 until January 2008.

Then something unexpected happened. Kabwe became a hero for speaking his mind. Crowds greeted him in the rain in Dar es Salaam to cheer him on after he was suspended. Leaders of four opposition parties supported Kabwe in a rally in September. Kabwe's party hired a helicopter so he could tour the country and his party could capitalize on his charisma. A ruling-party leader, Jaka Mwambi, warned fellow party members that Kabwe was popular despite his “red card” in parliament and even some ruling-party members were cheering for him.

“The press contributed a lot,” says Kabwe, recalling the drive to reinstate him. “Two hundred thousand people demonstrated in the streets of Dar.”

Under public pressure, President Kikwete formed a new presidential committee in November to investigate mining law. To the nation's shock, Kikwete appointed Kabwe to the 11-member team. “The mandate was given to look into the contracts, to look into the policy, to look into the legal regime, to look into the fiscal regime of the sector,” says Kabwe. “I came to know the sector very well.”

He also came to know Barrick.

The commission ended in 2008 and published a widely-cited document called the Bomani Report. It highlighted numerous flaws in the country's mining agreements, suggesting that villages around Tanzania's gold mines haven't benefited from foreign investment as they should have and that the government was misguided when it sold Barrick its final five per cent share of Bulyanhulu soon after the giant entered the country. The report recommended the government increase royalties and grant fewer tax exemptions.

Parliament began to discuss a new Mining Act.

In 2009, Barrick provided $10,000 in materials to repair a school in Kabwe's Kigoma North constituency.

Kigoma North is far from gold. Its only notable asset is an opposition MP who declares himself socialist, has enough power to threaten the terms of Barrick's contracts and wields so much public support even the president tries to get on his good side.

Cheaper than taxes

Barrick needed to get on Kabwe's good side, too. He was a respected economist and he was instrumental in drafting a new Mining Act parliament finalized in April 2010. Investing in Kabwe's school was a low-cost way for Barrick to show it had no ill will.

Teweli says the investment was part of Barrick's Heart of Gold fund, which pays for miscellaneous projects like art workshops with street children in Dar es Salaam. He says the Kigoma North government submitted a proposal and Barrick funded it because Kigoma North's education system is lagging behind national standards. Kabwe had complained about the same issue in parliament for years, with no effect.

Barrick found Kabwe much less confrontational than observers expected when MPs were drafting the new act. “During the writing of the new law, we worked together so well because we had to create a win-win situation,” says Kabwe. “So the enmity between us had to end.”

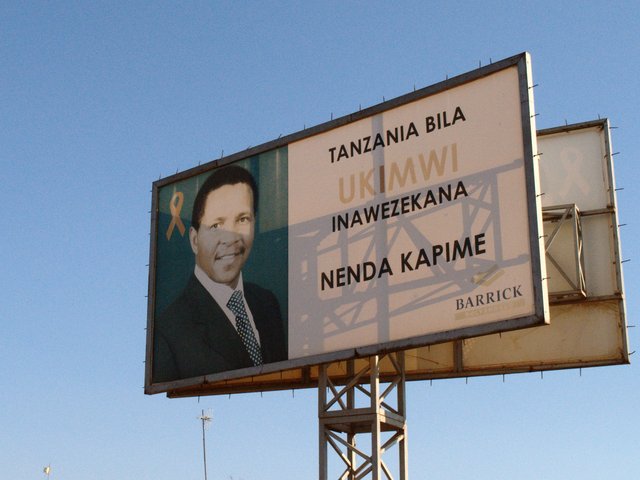

The president, too, gained politically from Barrick while mining debates flared. Barrick's billboard near Bulyanhulu leading to the 2010 election presented thousands of villagers with a giant picture of President Kikwete's face, complete with a “Barrick Gold” logo in the corner. Barrick says the sign is part of an AIDS awareness campaign launched in 2007. And in January 2010 President Kikwete cut the ribbon at Masengwa Secondary School near Kahama. Barrick renovated the school for $213,000 after Kikwete visited and publicly suggested someone should repair it.

Under the 2010 mining law, companies have to pay royalties of four per cent on gold exports, up from three per cent. Also, the government is to hold shares of all new foreign-owned mines. Barrick's mines are exempt from both rules, because the new law doesn't apply to Tanzania's existing mines.

Kabwe, recently re-elected and now Tanzania's go-to mining expert, doesn't criticize the result. When it passed, he told Reuters “it might send a negative signal to investors and might impact foreign direct investment. I'm worried on that.” Barrick doesn't criticize it either. When the legislative dust settled, both were victors. Barrick averted extra expenses at its mines. Kabwe became popular nationally and in his own district. They found their “win-win situation.”

Meanwhile, the Tanzanian government doesn't raise enough tax revenue to do its job. There's still no paved road crossing the country, one in ten children dies before turning five and according to a speech by president Kikwete in November 2010, only 14 per cent of Tanzanians have electricity. Debt stands at $11 billion as of December 2010, up $800 million from the previous year.

Barrick has some big numbers of its own, but they barely affect the country's budget. Tanzania exported $1.5 billion worth of gold in 2009, 40 per cent of the value of all Tanzania's exports, and most of that gold was Barrick's. But Barrick only paid $37 million in royalties and levies that year — about one per cent of Tanzania's total tax revenue of $3.27 billion. Employees paid another $37 million in taxes on their salaries.

The most glaring zero in Barrick's budget is corporate tax. Tanzania charges 30 per cent corporate income tax, but Barrick pays none because it hasn't recouped expenses as three of its mines aren't considered profitable yet. The fourth mine, Tulawaka, is profitable but Barrick cancels out the earnings with Buzwagi's expenses to delay paying corporate tax. Tanzania amended its income tax law in 2010 to prevent this sort of offsetting and it would now tax every gold mine individually, but Barrick keeps its existing arrangement. Only North Mara is expected to become profitable this year.

Aside from not receiving corporate income tax, Tanzania actually owes Barrick millions. In Tanzania, companies pay a “value-added tax” similar to Canada's GST when they buy goods and services and import fuel. As in Canada, the government owes a refund when companies pay more VAT than they collect from their customers. Barrick has no Tanzanian clients so it's entitled as of December 2010 to a total refund of $121 million that Tanzania over-collected over the years and can't afford to repay. It's more than one per cent of the country's official debt.

Barrick deflects Tanzanians' demands for more taxes by touting the trickle-down effect. It says it spent $69 million on goods and services from Tanzanian companies in 2009: proof that it's injecting money into Tanzania's economy and benefiting the entire nation. “Our biggest argument when dealing with government is convincing them that this is an issue about getting a bigger cake rather than trying to get more slices from the same cake,” says Teweli.

Barrick survives criticism even though the two Tanzanian ministers responsible for the Buzwagi deal, Msabaha and his successor Karamagi, are politically kaput. Both ministers resigned in February 2008 in the midst of a corruption scandal involving an energy contract with Richmond Development Company. Msabaha contracted Richmond Development, a briefcase company owned by Tanzanian businessmen and registered in the United States, to provide generators to alleviate Tanzania's frequent electricity outages. After the contract wasn't met Msabaha signed an even larger one, which Karamagi upheld.

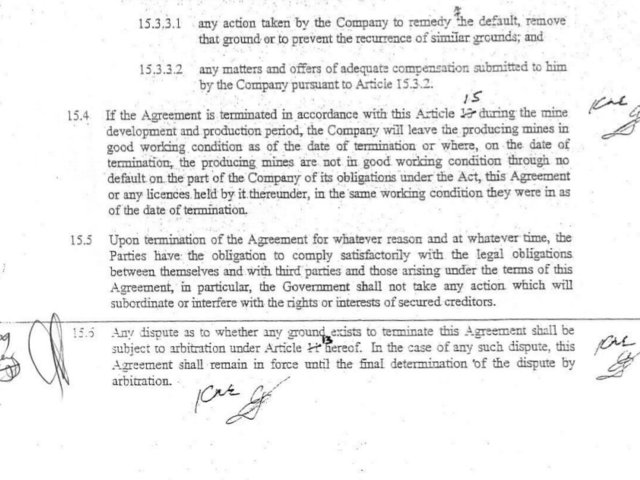

Parliament and Tanzanians abhor Karamagi's signature, but the ink on the Buzwagi contract, including Karamagi's last-minute scribbles in the margins, has proved permanent.

Barrick mined 716,000 ounces of gold in Tanzania in 2009, contributing roughly $300 million to the company's global revenue. The same year, it spent $3 million on corporate social responsibility projects in Tanzania to help keep the deal in place.

Drive-by

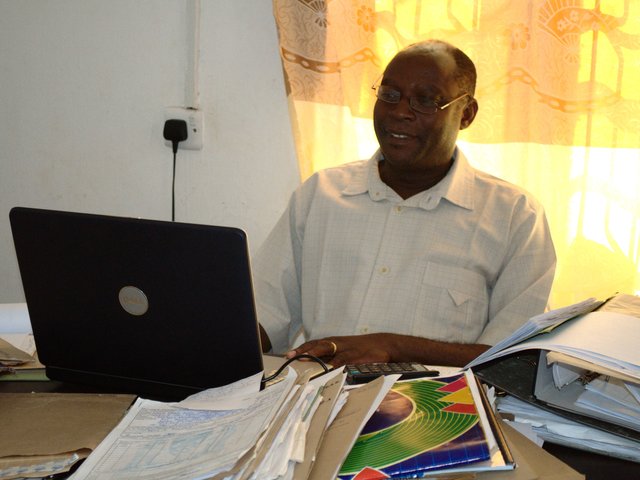

Teweli sits in the back seat of an SUV. A journalist chatters something to him in Swahili. Teweli answers the question and points out the window at Barrick's contribution to the region.

Reggae blares from a music store through the window as the SUV passes a market street near Bulyanhulu. Shops sell cheap televisions, pirated DVDs and cold Coca-Cola. Tanzania has seen its share of gold rushes, but only Barrick's brought refrigeration.

The SUV stops for a “courtesy call” at the village authorities' office, a bare building with a side-alley entrance. Now we have electricity, the authority says in Swahili. Now we have an AIDS centre.

He can't estimate how many people came to the village in the past decade, though, or the amount of new business, or whether residents' average income has changed. “They don't have statistics,” Teweli says. “When the district needs to prepare its reports, for the areas that are close to the mine they come to the mine for statistics.”

Ten years ago Barrick Gold was a ray of hope in Tanzania. It would bring prosperity, both in the impoverished villages around its mines and in the country's wretched treasury. Barrick has invested well over $1 billion in Tanzania, according to the presidential commission. Barrick's gold counts for more than a quarter of the value of all Tanzania's exports in 2010, and Barrick says it spent $69 million on goods and services from Tanzanian-owned companies in 2009. But Tanzania's balance sheet is only worsening. And as far as corporate social responsibility goes, sometimes image can substitute for substance.

Where security is an issue, projects are tangible. Villages around Barrick's Tanzanian mines are extremely poor while the mines themselves hold massive wealth. Thieves and vandals plague each mine and the best defence is a good reputation. Barrick installed water taps at Bulyanhulu so villagers wouldn't vandalize the pipeline, and it hired vigilantes at Buzwagi to build a rapport in the surrounding villages. It's loaning more than a million dollars to local miners near North Mara so they can acquire training, buy proper equipment and stop harming the environment and themselves with traditional mining chemicals like mercury. North Mara still experiences mass break-ins and that's why Barrick is investing there, according to project leader Philbert Rweyemamu in Barrick's Dar es Salaam offices.

Dar es Salaam is where Barrick needs to gain the nation's confidence and guard its mining contracts. It started on the wrong foot when it acquired Sutton Resources and inherited allegations of burying local miners alive at Bulyanhulu. A vocal national movement against foreign mining companies sprang up. Christian and Muslim groups from outside and within the country said Barrick harmed the environment, dealt in death and avoided paying the country a fair share. Tanzanian activist lawyers added to the problem by suing on behalf of families of allegedly-buried miners around Bulyanhulu. If international voices were the only ones criticizing Barrick, that wouldn't be too big a deal. But vocal Tanzanians can stir the radios, televisions, newspapers and gossip circles of Tanzania into a frenzy. Barrick holds contracts with government signatures on them, but those contracts don't seem solid when the populace rages at its government to change them.

Barrick could be a boon to the country, since it provides thousands of jobs and buys food and materials from local businesses. But it's hard to see long-reaching effects after a decade in Tanzania, and Barrick can't keep saying benefits are right around the corner. It needs to make Tanzanians happy, quickly and cost-effectively.

Enter corporate social responsibility. Barrick earns a social license to mine when Barrick's schools teach, Tanzania's activists deactivate and MPs say nice things. That's why Teweli is in the SUV showing off schools, electricity and an HIV clinic, in the same seat where he's shown the projects to dozens of Tanzanian journalists and MPs.

Results are mixed. The National Council of Muslims in Tanzania switched from criticism to respect after Teweli took representatives on the tour. Evans Rubara, a prominent journalist affiliated with the Christian Council of Tanzania, hasn't agreed to tour yet. Popular MP Zitto Kabwe discusses all angles concerning foreign mining companies. Tundu Lissu, an activist lawyer known for suing Sutton Resources on behalf of the families of allegedly-buried miners, doesn't. He was elected as MP in Singida, a gold-rich region of the country that foreign mining companies are exploring.

By convincing some critics Barrick's efforts are fruitful, Teweli has thrown a wedge into Tanzania's commentary. Some groups remain anti-Barrick and others speak with nuance, so ordinary Tanzanians hear a range of opinions and are ultimately less likely to demand wholesale change.

The same applies in Canada. Liberal MP John McKay introduced private member's bill C-300 in the House of Commons in 2009 and Parliament defeated it last October by a mere six votes. Had it passed, Canada's Ministers of Foreign Affairs and International Trade would have gained a mandate to investigate grievances against Canadian mining companies abroad. When citizens downriver of North Mara complained Barrick leaked chemicals into the water and their cows died as a result, for example, they could have brought their case to the Canadian government. Investigations would cost Canadian mining companies time and money, and if the companies were found guilty of human rights or environmental abuses Canadian officials could deny them loans and diplomatic support. The Canadian High Commission in Tanzania, for instance, has written columns and its commissioner has appeared on television when anti-Barrick rhetoric flared. If C-300 had become law and Canada's government had found Barrick guilty, the high commission media appearances might have stopped.

The bill was about corporate accountability for negative effects of mining. Mining lobbyists shifted the debate away from human-rights abuse allegations (which haven't been proven to Canadian standards, hence the bill) and toward corporate social responsibility and the good Canadian mining companies do overseas. The Prospectors and Developers Association of Canada and the Mining Association of Canada pointed to schools as evidence that Canadian mining companies are “actively engaged in Corporate Social Responsibility practices.” Conservative MPs mentioned schools when they spoke against C-300 in parliamentary debates.

Schools are a red herring in these debates, since they don't address allegations of human rights and environmental abuses. In a sense Mwendakulima High School is a red herring in Tanzania, too, since it doesn't address the teaching problems in the education system.

On the ground, Barrick's image hides a side-effect: expectations. Community relations staff from the back of the SUV say sick villagers come to Bulyanhulu, not to the hospital, expecting help with treatment. The community expects water and electricity from the mine, not the government. The school expects books from Barrick, not from the education system.

The government leaves spending in Barrick's hands because it can. Teachers at Barrick's school near Bulyanhulu told the government for three years they needed textbooks, to no avail. Facing an embarrassing blemish on its image, Barrick bought the books itself. To the government, that freed money to be spent elsewhere.

The same transfer of power happened with electricity. Barrick brought electricity to Bulyanhulu mine a decade ago assuming the national provider would run a few kilometres of wires from the mine to the communities around it. The villages stayed dark. Barrick finally ran the wires itself in 2009.

Ironically, Barrick is obliged to fund some of these projects because the government negotiated it. The mining agreements dictate that Barrick must spend $200,000 per mine per year on community projects. The politicians who negotiated the deal can take credit and Barrick can boost its corporate social responsibility image. Meanwhile the government takes a back seat as Barrick develops its community.

As the government shifts the business of keeping communities healthy and happy to Barrick, the company gains new privilege. Ten years ago Tanzanian politicians stood to gain if they threatened to expel Barrick from the country, knowing the people were on their side. Today Barrick can threaten to leave, forcing self-interested politicians to compromise or face voters' fury.

Villagers near Bulyanhulu bring their grievances to the people who can help them. These people cross the country in a private jet and roam villages in SUVs but they're not politicians. They're responsible to voting shareholders, not voters, and if they play their cards right they'll glad-hand in Toronto, not their constituencies.

The media-tour SUV passes a Barrick-built police station, a Barrick-built market and a Barrick-built dispensary. A Barrick-run bus kicks up dust as it travels the other way.

“We've become a surrogate government,” Teweli says from the back seat.